Creating a DevStream (dtm) Plugin for Anything

Yes, the title of this post isn’t bluffing: you can actually create a plugin for just about anything that takes your fancy.

In my previous article, I walked you guys through DevStream’s codebase.

If you haven’t read it yet, here’s a quick link for you:

In this blog, we will walk you through the steps of creating a DevStream plugin from scratch with an example.

What is DevStream

DevStream is an amazing tool that lets you install, update, manage, and integrate your DevOps tools quickly and flexibly.

Not to brag, but with DevStream, you can have your own DevOps toolchain that is specifically tailored to your need up and running in 5 minutes.

Don’t believe it? Check out our docs and follow the quickstart guide!

Existing Plugins

At the moment of publishing this article, we already support the following tools:

- Trello (including integration with GitHub)

- Jira (integration with GitHub)

- GitHub Repository bootstrapping (for Go)

- GitHub Actions (for Go, Python, and Nodejs)

- GitLab CI (for Go)

- Jenkins (installation)

- ArgoCD

- ArgoCD Application (the deployment of your apps)

- Prometheus + Grafana

- DevLake

- OpenLDAP

We aim to have 50 plugins at the end of 2022!

Check out our README for the latest status.

Why Would I Want to Create a DevStream Plugin

Wait. YOU ALREADY HAVE TONS OF PLUGINS! Why on earth would I want to create yet another one?

I agree with you.

Can I get a show of hands, who here has made a DevStream plugin before?

Very few, if any, I guess.

However (I know it’s just a fancy “but”), there are, in fact, things that you want to build a plugin for:

- Maybe you are building a nice and shiny DevOps tool, and you want to be able to set it up quickly without any hassle. You would have to write some automation scripts for it anyway, right? DevStream got you covered.

- Maybe you even need to integrate your tool with other tools to get the most out of it and you really don’t want to reinvent a lot of wheels just to manage those boring integrations. Again, DevStream got you covered.

- Maybe you have both internal tools and open-source tools whose installation and integration need to be automated. The open-source tools are fine, but how to manage those internal ones and integrate them? DevStream got you covered.

Or, maybe you just want to learn Go’s plugin, become a contributor, join our community and earn your certification (maybe a small present, too, who knows.) No problem.

No matter what your intention is and what thing you want to achieve, DevStream got you covered.

So hang tight, let’s get started.

Design: A “Local File” Plugin

In this example, let’s build something dum but simple, just to show you the process of creating a plugin.

We are creating a “local file” plugin. You specify the name and the content, and the plugin will create a local file for you. Let’s decide how we are going to use this plugin:

|

Basically:

- the name of the plugin:

localfile - options of the plugin:

- filename

- content

The plugin will create a file with desired content according to this piece of config.

Scaffolding Automagically

First, let’s clone the DevStream repo and generate some scaffolding code:

|

There will be some useful output to guide you through the whole process.

Now, if we do a git status, we can see some new stuff are already created automagically:

|

Let’s have a quick recap of the directory structure:

cmd/

cmd/plugin/localfile/main.go is the main entrance of your plugin. But here you don’t need to do anything; nothing.

dtm has already generated the code for you, including the interfaces that you must implement.

docs/

docs/plugins/localfile.md is the automatically generated documentation.

Yep, I know dtm is automagic, but it can’t read your mind. I’m afraid that you will have to write your own doc.

But hey, at least here you get a reminder that you need to create a doc :)

internal/pkg/

internal/pkg/plugin/localfile has your plugin’s main logic.

Here, we need to:

- define your input parameters (options);

- implement the validation of the input parameters;

- implement four mandatory interfaces.

Core Concepts

Config/State/Resource

Before explaining interfaces and implementing them, let’s have a look at how DevStream actually works:

- Config is a list of tools, each of which has a name, plugin, options, etc.

- State is a map containing each tool’s name, plugin, options, etc. It’s used to store the result of

dtm’s last action. - Resource is the tool that the plugin created. The

Readinterface returns a description of that resource, which should be the same as the State if nothing has been changed afterdtm’s last action.

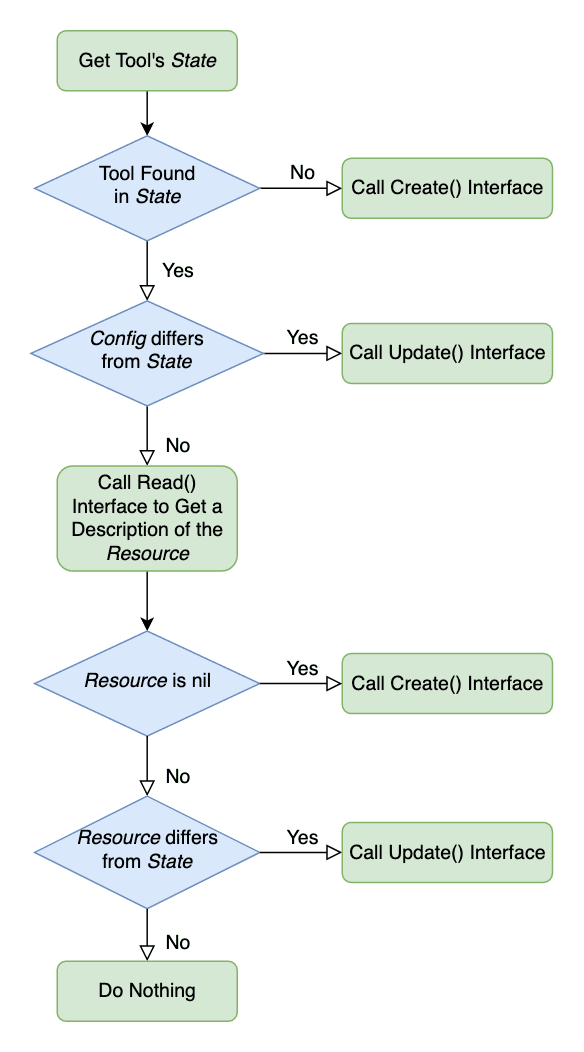

DevStream decides what to do based on your Config, the State, and the Resource’s status. See the flowchart below:

Interfaces

A quick recap: each DevStream plugin must satisfy the following four interfaces:

CreateReadUpdateDelete

Return values:

CreateandUpdatereturn two values(map[string]interface{}, error). The first return value is considered as the State, which will be stored in DevStream’s state file.Read’s first return value is a description of the Resource, which should be the same as the State if nothing has changed.Deletereturns(true, nil)if there is no error; otherwise it returns(false, error).

Coding

Input Options/Validation

Now let’s open internal/pkg/plugin/localfile/options.go and add options according to our design in the previous section.

The internal/pkg/plugin/localfile/options.go should look like:

|

Let’s also implement the validation function of the input options.

Open internal/pkg/plugin/localfile/validate.go and change the logic to verify the options. It should look like this:

|

Create()

We want to create the file based on the input options. So, let’s do just that in the file internal/pkg/plugin/localfile/create.go.

OK, talk is cheap, show me the code:

|

If you compare the code above to the code generated by dtm develop, you will see that we basically did nothing here. We only filled some blanks which are marked by dtm’s comment. The same is true for all the other interfaces.

A small tip: here, we can put the function writefile in internal/pkg/plugin/localfile/localfile.go, so that the code is better organized.

The localfile.go will look like this:

|

Read()

Let’s also implement the Read interface.

The logic is simple: we want to try to see if the file exists or not, and if yes, what’s the filename and content.

internal/pkg/plugin/localfile/read.go:

|

On the return value:

- If the file doesn’t exist, return nil, no error, because it means the resource hasn’t been created yet (or deleted by somebody)

- If the file exists, return the “status” of it and no error.

- Otherwise, return nil and the error.

Update()

Update will be triggered if Read returns a different result than what’s recorded in the State.

For the implementation, since we are updating a file, it’s the same as Create, so we can actually reuse it here without duplicated code:

internal/pkg/plugin/localfile/update.go:

|

Delete()

Last but not least, let’s implement the Delete interface.

internal/pkg/plugin/localfile/delete.go:

|

Just delete the file; nothing to look at here.

Build

Now that we finished coding, let’s build our new plugin. Our Makefile now supports building a specific plugin only:

|

Test

First, let’s create a config file config-localfile-test.yaml:

|

Now, let’s apply:

|

As we can see, the plugin has created our file successfully. To verify, you can open the “foo.txt” file to have a look.

If we apply again, nothing should happen, since the file is already created with the desired content:

|

But, what if somebody changed the content of “foo.txt”? Let’s experiment:

|

We can see that the file has drifted from the state, so it will be updated. After the operation, the file’s content is changed back to what we defined in our config.

Heck, let’s even try deleting this file and see what happens:

|

Apparently, DevStream thought the file should exist according to the state, but it doesn’t, so it is created again.

Last, let’s try to delete this file with dtm:

|

Hooray!

Summary

I’m sorry that I put the “TL;DR” at the end; it’s only because I want you to have a global feeling of DevStream. But for advanced developers, here’s a “TL;DR” (or use it as a checklist) for you:

- Run

dtm develop create-plugin --name=your-plugin. - Do a

git status, then:- find the generated files

- edit/code at the places where there is already a comment mark

- Pay special attention to the return value of the interfaces. Figure out the relationship between State and Resource. What the interfaces return decides how this plugin will behave.

- Last but not least, update the documentation.

If you enjoy reading this post, please like, comment, and subscribe! I will see you next time.